The Stone Houses of Chester, Vermont

How a 19th-century masonry technique from Scotland created a treasure trove of rare buildings in Chester, Vermont.

Driving along North Street in Chester, you can’t help but notice the half-mile-long parade of snecked ashlar buildings, including the town’s oldest example, the 1834 Ptolemy Edson House (background), and the 1840 Gideon Lee House (foreground), which is now an Airbnb.

Photo Credit : Greta RybusWhen it comes to building houses, you don’t have to be a little pig or a big wolf to know that wood beats straw and brick beats wood. But for the lucky folks of Chester, Vermont, there’s something even better than brick: stone. The town is home to a unique collection of snecked ashlar buildings, whose aesthetic qualities elevate them beyond simply being well-built and strong and into the realm of folk art. Composing the Stone Village Historic District, 10 of them line Route 103, known locally as North Street, with another 40 or more scattered throughout the surrounding area of south-central Vermont.

First, some definitions. “Ashlar” is cut and dressed stone, and it makes sense that the word comes down from the medieval Latin arsella, meaning a little board or shingle, since ashlar stones are usually laid up in horizontal bands. “Snecked” is a bit funkier, if Scottish dialect can bring the funk. In Scotland, a sneck is a latch or small bolt used to secure a door. In a snecked ashlar wall, relatively thin stones of different sizes make up the exterior surface pattern. The smallest ones—the snecks—serve both to fill in the gaps left by the bigger ones and, crucially, to penetrate through to an interior rubble wall, not unlike a series of bolts, acting the way metal ties do in a modern brick veneer wall.

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

But what, pray tell, is a Scottish word doing in Vermont? Like so many American things, the word and the building technique it describes came in thanks to immigration. Snecked ashlar construction is common in Scotland and the border lands with England, where tough weather and a relative lack of trees make it a natural choice. Scottish masons first arrived in Canada in the early 1800s, bringing their skills to bear on forts and canals, where stone outdid wood. In the early 1830s, some of them were hired to build a large stone factory in Cavendish, Vermont, just north of Chester.

Word must have spread quickly, because in 1834, Dr. Ptolemy Edson, a forward-minded leading figure in Chester, hired local brothers Addison and Wiley Clark to build him a Federal-style home using the new (to the Vermonters) technique. The brothers, part of a family with Scottish roots that had been in Vermont since the 1700s, likely learned snecked ashlar construction from their overseas kinsmen, possibly even on the Cavendish job. It’s been said that Edson paid each of his masons $5 a week, along with a gallon of good rum.

It’s not known whether Edson was taken by the technique’s novelty, its looks, its snugness against the huff-and-puff of Vermont winters, or something else, but he became a snecked ashlar booster to his neighbors. Addison and Wiley Clark—joined by a third brother, Orrison, as well as Arvin Earle and other colleagues—built stone buildings at about a one-a-year clip for the next decade, lining a half-mile stretch of North Street with Federal and Greek Revival residences, a one-room schoolhouse, and the village’s centerpiece, the First Universalist Church of 1845, which seats 300.

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

The Clarks surely must have appreciated the economic advantage of a building material that was literally underfoot and more or less free for the taking. Nearby Mount Flamstead, where they lived, is rich with gneiss and schist, metamorphic stone that splits relatively easily into angular pieces, better for facing a building than for wall-building. They and their farmer neighbors took it from the surface or from shallow quarries, harvesting it off-season and transporting it over the snow by sled in preparation for the summer construction season.

Modern renditions of snecked masonry adhere to a strict protocol using three sizes of stone. The Scottish master stonemason Bobby Watt describes them as “jumpers” or “risers” (square, or almost square, or up to three times as long as they are high); “levelers” (usually at least twice as long and up to five times as long as they are high); and “snecks”(smaller pieces that enable the mason to make up the differential in height between the top surfaces of the levelers and the risers). Laid up horizontally, the different-height stones key the rows together to make a strong wall.

The work of the Clarks and their friends is far looser and free—and sometimes downright exuberant, with huge risers surrounded by a bevy of attendant levelers and snecks, a pair of triangular stones kissing to form a vertical bow tie, and parallelogram levelers interlocking in a line. Everywhere is the interplay of the stones’ color and texture, with glimmers of mica across every facade. You can almost hear the delight of the crew as they grabbed the perfect next stone from the various piles they’d assembled. (Maybe the rum helped.)

Holding it all together was the mortar, apparently a secret recipe. Some reports have it containing moss; others describe slaking the lime slowly over fires of green wood. Whatever the trick, it worked, as most is still sticking strong after nearly two centuries. When the exterior walls were complete, carpenters moved in to hang timber joists from wall pockets in the interior. Walls were furred out, providing some insulative air space, and lath and plaster made for smoothly finished rooms befitting a prosperous town such as Chester.

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

Photo Credit : Greta Rybus

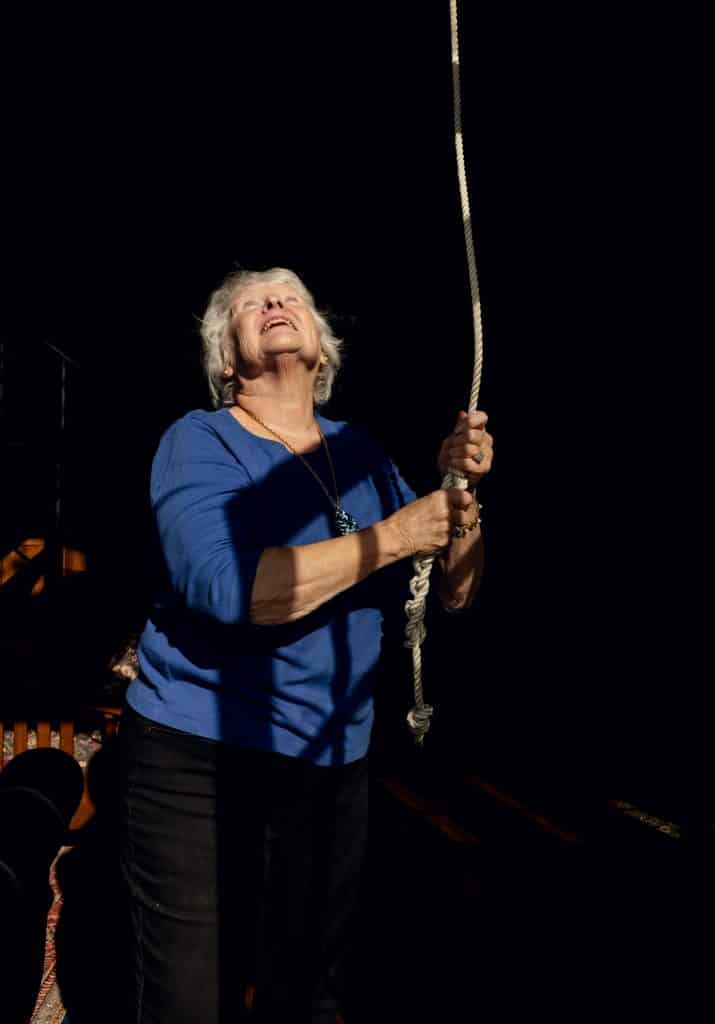

Like ardent art enthusiasts, today’s residents cherish and celebrate their pieces of folk sculpture. Nicholas Boke, former minister of the First Universalist Parish, happily shows the spot in the side pews where a farmhand used to lean his freshly bear-greased head against the stone wall. A square piece of wallpaper would be put up to cover the stain, only to be quickly soaked through. It took a full renovation to conquer the problem.

In 2019, Joanne Young and her husband, Mike, moved into the belfried schoolhouse at 186 North Street that she had attended back in the 1950s, converted to a home by a previous owner and complete with the 48-star flag she pledged allegiance to as a first-grader. Just across the street, at 189, Polly and Ian Montgomery have restored the Gideon Lee House into a five-star Airbnb outfitted with solar panels and Tesla batteries.

And at 146 North Street, Jon Clark, president of the Chester Historical Society, shows off the room where the original owner once sold sheepskin boots and moccasins he made on-site, his sheep on the hillside behind the house. The 14-stone arch over the front door commemorates Vermont’s place in the Union.

“I love the Stone Village,” Clark says. “And my next project is to finally figure out if I’m related to the guys who built it.”

Visiting Chester, Vermont

Exploring on foot: Walking-tour brochures created by Chester Townscape, a committee of the Chester Community Alliance, can be found at many locations around town as well as by going to chestervt.gov.

Staying overnight: The writer and the photographer for this story each spent the night in a historic stone building in Chester: the Gideon Lee House and the Cairn of Vermont cottage, both of which can be found at airbnb.com.

Bruce Irving

Bruce Irving is a Massachusetts-based renovation consultant and real estate agent who also served as the producer of "This Old House" for nearly two decades.

More by Bruce Irving