The Telling Room in Portland, Maine | On a Mission to Amplify Young Voices

With over 35,000 participants since its founding in 2004, The Telling Room in Portland, Maine, helps young people share their stories through writing.

In a publishing workshop overseen by teacher Jude Marx, right, students consider the sequence of poems, stories, and essays for the 2024 Telling Room anthology This Moment and the Next.

Photo Credit : Ryan HynesI want to show you a special place on this fine spring morning in Portland, Maine. Walk south on Exchange Street in the heart of the Old Port. The one-way street is just shy of a quarter mile as it stretches to Casco Bay and spills out near Commercial Street. This is the Portland that brings endless streams of visitors. But this is not the special place I want to show you.

Follow me a few blocks west on Commercial Street, away from ferries steaming to the islands, away from the boutiques and tourists. There, at 225 Commercial Street, nestled between a men’s clothing store and a shop selling wine and cigars, is a five-story brick building with tall windows facing the water.

We climb steps to the second floor. The sign on the door reads “The Telling Room.” Before we go in, take a moment to imagine being young and leaving behind everything you have known—friends, family, landscape, language—to come to a new country, and having few ways to express what you have seen and endured along the way. And even then: Who would listen or understand? Loneliness is a part of your new life, like the snow and the cold.

Photo Credit : Ryan Hynes

Or imagine growing up in a small Maine town while wrestling with questions of sexual or gender identity, knowing kids in school talk about you, feeling as much an outsider as if you had arrived from another continent, too.

Or simply imagine being young, and not knowing what lies ahead for you.

Now: Imagine opening this door intoa place where you can sit beside someone who will help you writethe stories that have stayed inside you for so long, you sometimes don’t remember they are there. A place where, after you hear others share their lives, you can take a breath and begin telling about your own—and everything changes.

It is here, in this place called TheTelling Room, that young people are asked to be brave. To trust others. To know that they can tell their stories, and to believe their stories matter.And for the past 20 years, The Telling Room has shown them how. That’s what waits on the other side of the door.

And there’s no place quite like it anywhere.

———

“We’re dealing with all this heavy stuff, but it’s all driven by the stories that kids need to tell and are compelled to tell and urgently want to tell.” —Michael Paterniti, cofounder of The Telling Room

———

To understand what happens at The Telling Room, which has seen more than 35,000 young people take part in its programs all across Maine, let’s step back a few decades. Creative newcomers are putting down roots in Portland, and ideas and energy are everywhere. One day in 2004, three people are sitting in a booth at a Congress Street café. They are in their mid-30s, and two are a married couple: Michael Paterniti and Sara Corbett, both accomplished journalists as well as the parents of two preschoolers. With them is their friend Susan Conley, an author and a passionate teacher of writing. She grew up in midcoast Maine and, after teaching in Boston, moved to Portland with her husband and their two preschool-age children.

At this time, Portland is seeing an influx of writers, artists, musicians, makers, and chefs. But also arriving in the city is the first big wave of asylum seekers from Africa, Afghanistan, and the Middle East—families who had fled the kind of danger and turmoil that Paterniti and Corbett had both reported on. “I found the same young people I had seen in Sudan now on the other side, in Portland,” Paterniti tells me now, 20 years later. “You would see the end of their journey here. It felt really vital that we help them tell their story.”

Paterniti and Corbett have recently returned from a village in Spain, where they spent hours in a cave set deep in a hillside. Inside was a special space, El Contador, literally “the counting room,” which also translates as “the telling room.” There, they heard stories by a man named Ambrosio who held his listeners spellbound.

Sitting in the café, the trio begin talking about their belief that children are natural storytellers who need their own “telling room” to discover their voices. “We wanted to show them the path,” Conley remembers. So they hatch an idea: Start a nonprofit writing center where young people can come for free and learn how to unlock the stories they had lived.

Photo Credit : Ryan Hynes

The problem was, as Conley puts it, “we had all these wild ideas, but we had no students.” So they begin meetingwith teachers throughout the city, telling them, “Many students feel unheard, not seen. Let us help you reach them.”

Theyvolunteer in high schools, middle schools, elementary schools. They work with kids who’d been in Maine all their lives as well as those who had just landed here, with a new language to learn. Calling their project The Telling Room, they believe in their mission even in the face of its mounting obligations. “The conflict was, we’re writers. We have to write and produce,” Conley tells me.“And we were really, really overtired. It took a serious personal toll. But we kept hearing yes from teachers—We need you.”

Paterniti remembers Conley saying once, “It’s like we have seven tickets a day to spend. So you spend three tickets on family, three tickets on work. And we only have one ticket left for The Telling Room. Except The Telling Room is taking three tickets.”

“But we had to keep doing it, because it mattered,” he adds. “These kids were telling unbelievable stories. And there was this awe at how these kids were finding the words, the courage to tell these stories out loud.”

And then angels arrive:A foundation awards them $8,000. “It was life-changing,” Conley recalls. With the funds, they hirethe poet Gibson Fay-LeBlanc to be the first program director of a nonprofit writing center that doesn’texist yet. They applyfor more grants, small ones and then big national ones. Local businesses takenote. Donations come in. By 2007, The Telling Room finally has a place to call home—the sunny spaces on Commercial Street where it’s been ever since—and the ability to publish its first anthology of young writers’ work, I Remember Warm Rain.

Photo Credit : Ryan Hynes

An installation called the Story House Project launches that first book at Portland’s nonprofit SPACE Gallery. Students at the Maine College of Art & Design created posters to illustrate the writers’ words and built a series of sculptural “houses”—some representing what the writers had left behind, others showing the writers’ imaginings of what a home could be. Inside each house, audio of a story is playing.

One of these is stories by Aruna Kenyi. He is 16, maybe 17. He has spent hours with Paterniti, sitting beside him in a room at Portland High School, as Aruna spoke his words into a tape recorder. He told Paterniti about being 5 years old in South Sudan when soldiers burned his village. He ran and hid with his older brother in a cane field. He was certain his parents were dead. He hid and walked for more than a year before reaching a refugee camp, and then walked again when the camp became too dangerous.

After each session, Paterniti transcribed the tape so they could look together at the words in Aruna’s new language. Eventually, a way to put them into a story took shape. And now, for the first time, Portland will hear it.

In the house, Aruna’s audio begins: “I have no photographs of my past, none of my village or parents or me as a boy there, none of the places where we fled or the camps in which we lived, nor of my friends.” After Aruna came to Maine, the listeners learn, a letter arrived and inside was a photograph of his mother and father, still alive thousands of miles away.

Looking back on that night at the SPACE Gallery, Paterniti remembers it as a seminal moment for The Telling Room. “We all saw you can be vulnerable. You can be emotional. You can tell your story. All seems possible.”

———

“Who are the youth of Maine? What stories are we missing? There is a need for us to be here.” —Kristina M.J. Powell, executive director of The Telling Room

———

The day of my visit to The Telling Room begins with a field trip by fifth-graders from the Village School in Gorham, about 10 miles west of Portland. It is one of the 42 Maine schools that will reach out to The Telling Room this year. The kids wander around the large central loft, which is filled with light from tall windows. Chairs and shelves are painted cheery red and green. The sofas are deep and comfy, and the tables hold jars filled with pens and pencils. A poster on the wall sets out a simple ethos: “We Agree to: No Phones; Pen to Paper; Respect Other People’s Work; Don’t Hold Back.”

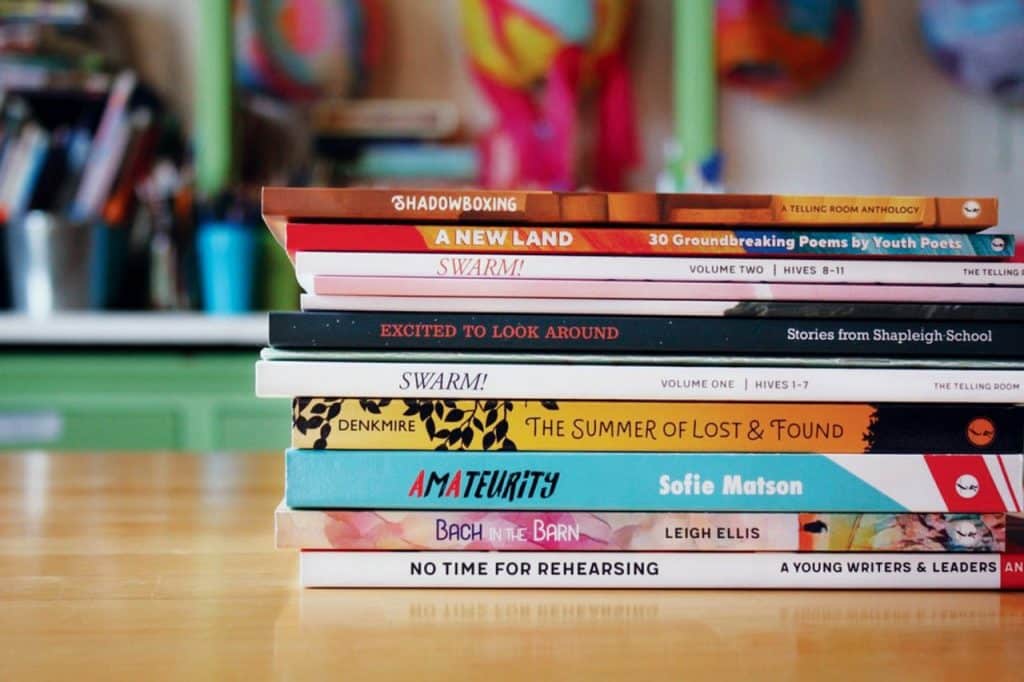

In all the rooms and offices, books line the shelves. They range from classics by the likes of F. Scott Fitzgerald to modern-day works by Telling Room mentors and visiting authors. But most precious here are the nearly 230 titles that hold the writings of more than 5,000 young people. Whatever else they do in life, their stories will live inside these books.

Photo Credit : Ryan Hynes

But to call them books does not do them justice. “Books” is a quiet word. The pages in these volumes are not. Instead, they are filled with voices. Some emerge from memories that have sometimes traveled across years and thousands of miles; others come from growing up in Aroostook or in fishing villages on the Maine coast.Here are stories from the Young Writers & Leaders program, focused on high school students with international backgrounds. Their stories slowly shift as the years pass: There are fewer tales of harrowing journeys to a new land, as their journeys now lead inward—the struggle not in the getting here, but in the being here. And here are novels and poetry collections and memoirs from the Young Emerging Authors program, in which four high schoolers each spend nearly a year creating just one work that becomes as polished and professional as if they were far older writers.

Whenever schoolkids visit, they learn about these books, written by young people just like them. The message is clear: You, too, can do this. And one way to begin is simply to look closely at the life swirling around you.

Before long, the kids from the Village School go outside with their teacher, Alison Penley, to walk around, to see the life of the Portland waterfront so they can come back in and write about it. Once inside theygrab pencils and paper and sprawl on the red carpet, or sit hunched at the tables. Telling Room teachers Kathryn Williams and Jack Gendron move from one to the next, helping to coax a few more words. “What do you want to happen next?” Williams asks one boy.

After a half hour, the children gather in a circle. Williams, who writes young-adult fiction and who has been teaching here for a decade, tells them, “I think writing looks like walking in the world and just eavesdropping. You know what writing is? It’s being curious. It’s asking, What if?”

Then she asks everyone to share something they had written. “Sharing your writing can make you feel a little embarrassed,” she tells them. “The more you share, the easier it becomes.”

One boy says he wrote about a pirate. Gendron, a poet, asks, “What do you think it is like to raise a pirate?” With a shy, proud smile, another boy reads about his father’s gold watch. A girl says she wrote a play about getting ready to go to a party.

I watch and think what The Telling Room wants to do with field trips like this is not to teach writing—the way it does during the months-long workshops. This is about striking a match, and hoping a spark may catch.

———

“When I came to The Telling Room it was a very powerful feeling, knowing that I could share my stories honestly, and feel like I would be listened to.” —Leigh Ellis, whose novel Bach in the Barn was published in 2021

———

By midafternoon during my visit, when the schools are out, high school students begin to arrive at The Telling Room. Four are in the Young Emerging Authors program, and I meet them in a small room where they are working under the final deadline for their 10-month project. There are three high school sophomores and one junior, high achievers who have signed up for the intensity of writing a solo book. Each has been working with a mentor under the direction of program lead Jude Marx and teacher Kathryn Williams.

They introduce themselves and their work to me. Josie Ellis’s poetry revolves around the theme of water. Margaret Horton’s novel features a heroine living in the last human settlement on earth. Madeleine Turgelsky has set what she calls her “sapphic novel” during the ’80s AIDS epidemic in New York. Natalia Mbadu’s memoir of struggling with faith is a mix of prose and lyrics.

Each of them has just received feedback from an outside reader, someone coming to their work for the first time, and they admit to me it can be scary to see new critiques after putting in so much effort. The room is quiet as they scroll through the suggestions. They have only two weeks to make changes. Soon their books will be off to a printer, ready for their own book launch and reading in September.

Photo Credit : Ryan Hynes

Marx sits beside Josie to discuss a problem her reader has flagged. Josie has written more than 30 poems, and while many address different people—her mother, her siblings, her friends—she uses “you” for nearly all. It’s a problem she needs to solve, and time is not her friend. “I want it to be perfect,” she says softly.

Outside in the big loft space, students in the Young Writers & Leaders program have gathered. Before joining them, I meet with Sonya Tomlinson, who has been with The Telling Room from the early days. On her bulletin board she has pinned group photos of every young person she has taught: 437 in all, from 57 countries. She talks about them as if they were family, and she admits she feels protective of these students, who—because she and co-teacher Hipai Pamba are very good at what they do—open up their lives to each other.

When I mention the challenges today of being an immigrant, Tomlinson stops me. “We do not use the word immigrant.We do not use the word refugee,” she says. “Our students told us they don’t want to be identified by those words. They don’t want people to feel pity for their hardships. We say our students are multilingual, multicultural. And for some that’s not their story. It’s their parents’ story.”

And because of that, she is sensitive to the fact that “students may reveal something to their family that they haven’t been able to express. And what they write lives forever. Your grandchild is going to pick this up and see who you were in 10th grade. So we talk about that.”

Tomlinson shows me apoem by a Muslim girl who no longer wants to wear the hijab. She feels that her mother is proud of her only when she dresses religiously, “and she doesn’t want to anymore,” Tomlinson says. “I told her, ‘I need to know you feel OK publishing this. Because your mom will read it.’ Her mother came to herreading, and afterward she found me to say thank you.”

Photo Credit : Ryan Hynes

At around 4, the students sit down in a circle with Tomlinson and Pamba. They read a snippet from the session’s writing prompt—where they find calm, or whether they’ve had a dream—and then they talk about what lies ahead. On this day, they are only a few weeks away from the program’s end. At a reading at the Portland Museum of Art later this month, they will see the new book Outbeam the Sun—their book—for the first time. “It doesn’t set in that they’re published authors until the book is in their hands,” Pamba, a former Telling Room student herself, tells me. “You look through and find your story and see your photo.”

In the circle, a number of the students admit they are nervous because soon they will stand on the museum’s auditorium stage and they will read. And for the first time, their family will hear their stories.

Pamba understands the nerves, but offers this advice: “When you finish reading, take a moment at the end and listen to the applause. Feel the awe.”

On this day, I keep hearing how The Telling Room believes in these students. That the teachers don’t tell them they’ll be a writer one day, but that they are right now.

———

“Without writing, I wouldn’t know what would be on my mind every day, what would give me the joy in my life…. Writing is my way of creating life.” —Sunila DeLoacth, writing at The Telling Room in 2024

———

Later that month, I return to Maine for the book launch and reading. The young writers’ photos are displayed on a big screen on the stage as one by one, they walk to the podium.

Here is Nevaeh Lynn-Rose Patt. She is 16. We hear about her childhood in the state of Washington where her mother often left her and her little brother on their own while she chased her next fix. Now she is with a new family she loves in Maine. But “I don’t want to forget that feeling of abandonment and loneliness. The person I am now was created by the person I was before.”

Here is Noemia Nzolameso, who tells about trying to fit in with white classmates and realizing she needs to be true to herself. Here is Faisal Azeez, his voice crisp and confident, telling about the growing distance he felt during the pandemic from the brother he loves.

Here is Angelique Kabisa, as composed as if she has done this all her life, reading about how she needs to be a success in life in order to honor the sacrifice her parents made to bring her here to have a chance at a better life.

And here is Cristina Zalabantu. She is 17 and came to Portland from Angola when she was 5. “As the Stars Watch” is a memory of a home she has never forgotten, the first story she has put out into the world: If welcome were a home, it would be our house. I remember not being able to fall asleep most of the time. The three of us slept in the kitchen. There was a little window where I could see the bright stars watching me as they reflected into the room. I loved watching the stars…

When everyone has read and the audience has stood and clapped, the young men and women take it all in from the stage as if in a theater—and in a way, they are. This is their moment in the spotlight. As I watch them in the hallway afterward clutching their books, I think about how every young person I have spoken with has told me how The Telling Room has changed their lives.

But I think about how for all these years, so many people reading and listening to them have also been changed. Because what the founders of The Telling Room always knew is something Paterniti once wrote years ago to Aruna Kenyi: You speak—and we listen, as if it happened to us.

To learn more about The Telling Room’s programs, events, and published works, go to tellingroom.org.

Mel Allen

Mel Allen is the fifth editor of Yankee Magazine since its beginning in 1935. His first byline in Yankee appeared in 1977 and he joined the staff in 1979 as a senior editor. Eventually he became executive editor and in the summer of 2006 became editor. During his career he has edited and written for every section of the magazine, including home, food, and travel, while his pursuit of long form story telling has always been vital to his mission as well. He has raced a sled dog team, crawled into the dens of black bears, fished with the legendary Ted Williams, profiled astronaut Alan Shephard, and stood beneath a battleship before it was launched. He also once helped author Stephen King round up his pigs for market, but that story is for another day. Mel taught fourth grade in Maine for three years and believes that his education as a writer began when he had to hold the attention of 29 children through months of Maine winters. He learned you had to grab their attention and hold it. After 12 years teaching magazine writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, he now teaches in the MFA creative nonfiction program at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Like all editors, his greatest joy is finding new talent and bringing their work to light.

More by Mel Allen